Particle in a spherically symmetric potential

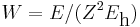

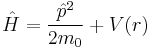

In quantum mechanics, the dynamics of a particle in a spherically symmetric potential has a Hamiltonian of the following form:

where  denotes the mass of the particle in the potential.

denotes the mass of the particle in the potential.

In its quantum mechanical formulation, it amounts to solving the Schrödinger equation with the potential V(r) which depend only on r, the modulus of r. Due to the spherical symmetry of the system it is useful to use spherical coordinates r,  and

and  . When this is done, the time-independent Schrödinger equation for the system is separable.

. When this is done, the time-independent Schrödinger equation for the system is separable.

Contents |

Structure of the eigenfunctions

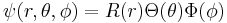

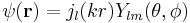

The eigenfunctions of the Schrödinger equation have the form

in which the spherical polar angles θ and φ represent the colatitude and azimuthal angle, respectively. The last two factors of ψ are often grouped together as spherical harmonics, so that the eigenfunctions take the form

The differential equation which characterizes the function  is called the radial equation.

is called the radial equation.

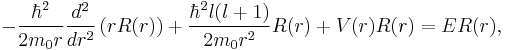

Derivation of the radial equation

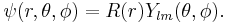

The kinetic energy operator in spherical polar coordinates is

The spherical harmonics satisfy

Substituting this into the Schrödinger equation we get a one-dimensional eigenvalue equation,

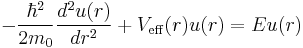

Relationship with 1-D Schrödinger equation

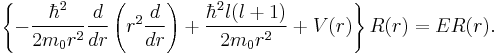

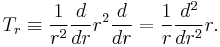

Note that the first term in the kinetic energy can be rewritten

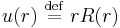

If subsequently the substitution  is made into

is made into

the radial equation becomes

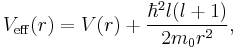

which is precisely a Schrödinger equation for the function u(r) with an effective potential given by

where the radial coordinate r ranges from 0 to  . The correction to the potential V(r) is called the centrifugal barrier term.

. The correction to the potential V(r) is called the centrifugal barrier term.

Solutions for potentials of interest

Five special cases arise, of special importance:

- V(r) = 0, or solving the vacuum in the basis of spherical harmonics, which serves as the basis for other cases.

(finite) for

(finite) for  and 0 elsewhere, or a particle in the spherical equivalent of the square well, useful to describe scattering and bound states in a nucleus or quantum dot.

and 0 elsewhere, or a particle in the spherical equivalent of the square well, useful to describe scattering and bound states in a nucleus or quantum dot.- As the previous case, but with an infinitely high jump in the potential on the surface of the sphere.

- V(r) ~ r2 for the three-dimensional isotropic harmonic oscillator.

- V(r) ~ 1/r to describe bound states of hydrogen-like atoms.

We outline the solutions in these cases, which should be compared to their counterparts in cartesian coordinates, cf. particle in a box. This article relies heavily on Bessel functions and Laguerre polynomials.

Vacuum case

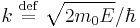

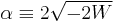

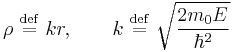

Let us now consider V(r) = 0 (if  , replace everywhere E with

, replace everywhere E with  ). Introducing the dimensionless variable

). Introducing the dimensionless variable

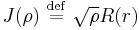

the equation becomes a Bessel equation for J defined by  (whence the notational choice of J):

(whence the notational choice of J):

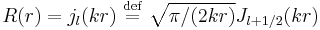

which regular solutions for positive energies are given by so-called Bessel functions of the first kind'  so that the solutions written for R are the so-called Spherical Bessel function

so that the solutions written for R are the so-called Spherical Bessel function  .

.

The solutions of Schrödinger equation in polar coordinates for a particle of mass  in vacuum are labelled by three quantum numbers: discrete indices l and m, and k varying continuously in

in vacuum are labelled by three quantum numbers: discrete indices l and m, and k varying continuously in  :

:

where  ,

,  are the spherical Bessel function and

are the spherical Bessel function and  are the spherical harmonics.

are the spherical harmonics.

These solutions represent states of definite angular momentum, rather than of definite (linear) momentum, which are provided by plane waves  .

.

Sphere with square potential

Let us now consider the potential  for

for  and

and  elsewhere. That is, inside a sphere of radius

elsewhere. That is, inside a sphere of radius  the potential is equal to V0 and it is zero outside the sphere. A potential with such a finite discontinuity is called a square potential.[1]

the potential is equal to V0 and it is zero outside the sphere. A potential with such a finite discontinuity is called a square potential.[1]

We first consider bound states, i.e., states which display the particle mostly inside the box (confined states). Those have an energy E less than the potential outside the sphere, i.e., they have negative energy, and we shall see that there are a discrete number of such states, which we shall compare to positive energy with a continuous spectrum, describing scattering on the sphere (of unbound states). Also worth noticing is that unlike Coulomb potential, featuring an infinite number of discrete bound states, the spherical square well has only a finite (if any) number because of its finite range (if it has finite depth).

The resolution essentially follows that of the vacuum with normalization of the total wavefunction added, solving two Schrödinger equations — inside and outside the sphere — of the previous kind, i.e., with constant potential. Also the following constraints hold:

- The wavefunction must be regular at the origin.

- The wavefunction and its derivative must be continuous at the potential discontinuity.

- The wavefunction must converge at infinity.

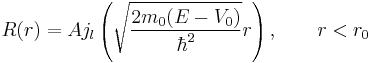

The first constraint comes from the fact that Neumann N and Hankel H functions are singular at the origin. The physical argument that ψ must be defined everywhere selected Bessel function of the first kind J over the other possibilities in the vacuum case. For the same reason, the solution will be of this kind inside the sphere:

with A a constant to be determined later. Note that for bound states,  .

.

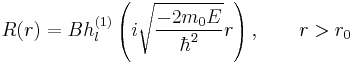

Bound states bring the novelty as compared to the vacuum case that E is now negative (in the vacuum it was to be positive). This, along with third constraint, selects Hankel function of the first kind as the only converging solution at infinity (the singularity at the origin of these functions does not matter since we are now outside the sphere):

Second constraint on continuity of ψ at  along with normalization allows the determination of constants A and B. Continuity of the derivative (or logarithmic derivative for convenience) requires quantization of energy.

along with normalization allows the determination of constants A and B. Continuity of the derivative (or logarithmic derivative for convenience) requires quantization of energy.

Sphere with infinite square potential

In case where the potential well is infinitely deep, so that we can take  inside the sphere and

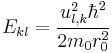

inside the sphere and  outside, the problem becomes that of matching the wavefunction inside the sphere (the spherical Bessel functions) with identically zero wavefunction outside the sphere. Allowed energies are those for which the radial wavefunction vanishes at the boundary. Thus, we use the zeros of the spherical Bessel functions to find the energy spectrum and wavefunctions. Calling

outside, the problem becomes that of matching the wavefunction inside the sphere (the spherical Bessel functions) with identically zero wavefunction outside the sphere. Allowed energies are those for which the radial wavefunction vanishes at the boundary. Thus, we use the zeros of the spherical Bessel functions to find the energy spectrum and wavefunctions. Calling  the kth zero of

the kth zero of  , we have:

, we have:

So that one is reduced to the computations of these zeros  , typically by using a table or calculator, as these zeros are not solvable for the general case.

, typically by using a table or calculator, as these zeros are not solvable for the general case.

In the special case  (spherical symmetric orbitals), the spherical Bessel function is

(spherical symmetric orbitals), the spherical Bessel function is  , which zeros can be easily given as

, which zeros can be easily given as  . Their energy eigenvalues are thus:

. Their energy eigenvalues are thus:

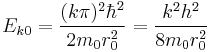

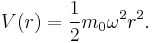

3D isotropic harmonic oscillator

The potential of a 3D isotropic harmonic oscillator is

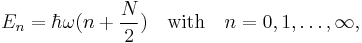

In this article it is shown that an N-dimensional isotropic harmonic oscillator has the energies

i.e., n is a non-negative integral number; ω is the (same) fundamental frequency of the N modes of the oscillator. In this case N = 3, so that the radial Schrödinger equation becomes,

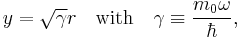

Introducing

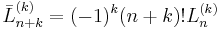

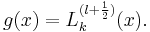

and recalling that  , we will show that the radial Schrödinger equation has the normalized solution,

, we will show that the radial Schrödinger equation has the normalized solution,

where the function  is a generalized Laguerre polynomial in γr2 of order k (i.e., the highest power of the polynomial is proportional to γkr2k).

is a generalized Laguerre polynomial in γr2 of order k (i.e., the highest power of the polynomial is proportional to γkr2k).

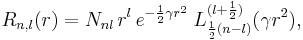

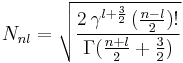

The normalization constant Nnl is,

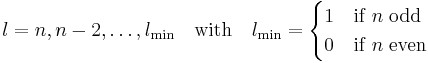

The eigenfunction Rn,l(r) belongs to energy En and is to be multiplied by the spherical harmonic  , where

, where

This is the same result as given in this article if we realize that  .

.

Derivation

First we transform the radial equation by a few successive substitutions to the generalized Laguerre differential equation, which has known solutions: the generalized Laguerre functions. Then we normalize the generalized Laguerre functions to unity. This normalization is with the usual volume element r2 dr.

First we scale the radial coordinate

and then the equation becomes

with  .

.

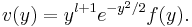

Consideration of the limiting behaviour of v(y) at the origin and at infinity suggests the following substitution for v(y),

This substitution transforms the differential equation to

where we divided through with  , which can be done so long as y is not zero.

, which can be done so long as y is not zero.

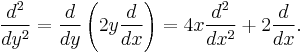

Transformation to Laguerre polynomials

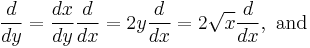

If the substitution  is used,

is used,  , and the differential operators become

, and the differential operators become

The expression between the square brackets multiplying f(y) becomes the differential equation characterizing the generalized Laguerre equation (see also Kummer's equation):

with  .

.

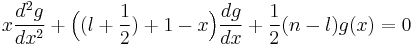

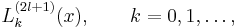

Provided  is a non-negative integral number, the solutions of this equations are generalized (associated) Laguerre polynomials

is a non-negative integral number, the solutions of this equations are generalized (associated) Laguerre polynomials

From the conditions on k follows: (i)  and (ii) n and l are either both odd or both even. This leads to the condition on l given above.

and (ii) n and l are either both odd or both even. This leads to the condition on l given above.

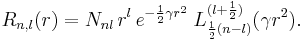

Recovery of the normalized radial wavefunction

Remembering that  , we get the normalized radial solution

, we get the normalized radial solution

The normalization condition for the radial wavefunction is

Substituting  , gives

, gives  and the equation becomes

and the equation becomes

By making use of the orthogonality properties of the generalized Laguerre polynomials, this equation simplifies to

Hence, the normalization constant can be expressed as

Other forms of the normalization constant can be derived by using properties of the gamma function, while noting that n and l are both of the same parity. This means that n + l is always even, so that the gamma function becomes

where we used the definition of the double factorial. Hence, the normalization constant is also given by

Hydrogen-like atoms

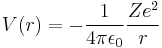

A hydrogenic (hydrogen-like) atom is a two-particle system consisting of a nucleus and an electron. The two particles interact through the potential given by Coulomb's law:

where

- ε0 is the permittivity of the vacuum,

- Z is the atomic number (eZ is the charge of the nucleus),

- e is the elementary charge (charge of the electron),

- r is the distance between the electron and the nucleus.

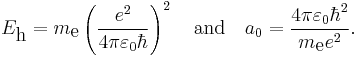

The mass m0, introduced above, is the reduced mass of the system. Because the electron mass is about 1836 smaller than the mass of the lightest nucleus (the proton), the value of m0 is very close to the mass of the electron me for all hydrogenic atoms. In the remaining of the article we make the approximation m0 = me. Since me will appear explicitly in the formulas it will be easy to correct for this approximation if necessary.

In order to simplify the Schrödinger equation, we introduce the following constants that define the atomic unit of energy and length, respectively,

Substitute  and

and  into the radial Schrödinger equation given above. This gives an equation in which all natural constants are hidden,

into the radial Schrödinger equation given above. This gives an equation in which all natural constants are hidden,

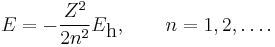

Two classes of solutions of this equation exist: (i) W is negative, the corresponding eigenfunctions are square integrable and the values of W are quantized (discrete spectrum). (ii) W is non-negative. Every real non-negative value of W is physically allowed (continuous spectrum), the corresponding eigenfunctions are non-square integrable. In the remaining part of this article only class (i) solutions will be considered. The wavefunctions are known as bound states, in contrast to the class (ii) solutions that are known as scattering states.

For negative W the quantity  is real and positive. The scaling of y, i.e., substitution of

is real and positive. The scaling of y, i.e., substitution of  gives the Schrödinger equation:

gives the Schrödinger equation:

For  the inverse powers of x are negligible and a solution for large x is

the inverse powers of x are negligible and a solution for large x is ![\exp[-x/2]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f2e31cc1692486c03f1faea6a017a7b9.png) . The other solution,

. The other solution, ![\exp[x/2]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/084f9d8edc78d96fb979332d94ffbaf2.png) , is physically non-acceptable. For

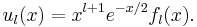

, is physically non-acceptable. For  the inverse square power dominates and a solution for small x is xl+1. The other solution, x-l, is physically non-acceptable. Hence, to obtain a full range solution we substitute

the inverse square power dominates and a solution for small x is xl+1. The other solution, x-l, is physically non-acceptable. Hence, to obtain a full range solution we substitute

The equation for fl(x) becomes,

Provided  is a non-negative integer, say k, this equation has polynomial solutions written as

is a non-negative integer, say k, this equation has polynomial solutions written as

which are generalized Laguerre polynomials of order k. We will take the convention for generalized Laguerre polynomials of Abramowitz and Stegun.[2] Note that the Laguerre polynomials given in many quantum mechanical textbooks, for instance the book of Messiah,[1] are those of Abramowitz and Stegun multiplied by a factor (2l+1+k)! The definition given in this Wikipedia article coincides with the one of Abramowitz and Stegun.

The energy becomes

The principal quantum number n satisfies  , or

, or  . Since

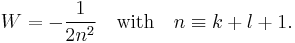

. Since  , the total radial wavefunction is

, the total radial wavefunction is

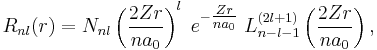

with normalization constant

which belongs to the energy

In the computation of the normalization constant use was made of the integral [3]

References

- ^ a b A. Messiah, Quantum Mechanics, vol. I, p. 78, North Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam (1967). Translation from the French by G.M. Temmer

- ^ Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1965), "Chapter 22", Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover, pp. 775, ISBN 978-0486612720, MR0167642, http://www.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_775.htm.

- ^ H. Margenau and G. M. Murphy, The Mathematics of Physics and Chemistry, Van Nostrand, 2nd edition (1956), p. 130. Note that convention of the Laguerre polynomial in this book differs from the present one. If we indicate the Laguerre in the definition of Margenau and Murphy with a bar on top, we have

.

.

![\frac{\hat{p}^2}{2m_0} = -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m_0} \nabla^2 =

- \frac{\hbar^2}{2m_0\,r^2}\left[ \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\Big(r^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\Big) - \hat{l}^2 \right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cebff6a5e193df0990f4bc7da1bf0f74.png)

![\hat{l}^2 Y_{lm}(\theta,\phi)\equiv \left\{ -\frac{1}{\sin^2\theta} \left[

\sin\theta\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \Big(\sin\theta\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\Big)

%2B\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \phi^2}\right]\right\} Y_{lm}(\theta,\phi)

= l(l%2B1)Y_{lm}(\theta,\phi).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/60c23b8124cc3fca3df748c62dc16df5.png)

![\rho^2{d^2J\over d\rho^2}%2B\rho{dJ\over d\rho}%2B\left[\rho^2-\left(l%2B\frac{1}{2}\right)^2\right]J=0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/948099a7eb7a34013da40664d0ce5417.png)

![\left[-{\hbar^2 \over 2m_0} {d^2 \over dr^2} %2B {\hbar^2l(l%2B1) \over 2m_0r^2}%2B\frac{1}{2} m_0 \omega^2 r^2 - \hbar\omega(n%2B\frac{3}{2}) \right] u(r) = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/71f24ba500e9656ff9eccbf7858b07f9.png)

![N_{nl} = \left[\frac{ 2^{n%2Bl%2B2} \,\gamma^{l%2B\frac{3}{2}} } {\pi^{\frac{1}{2}}}

\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}

\left[\frac{ [\frac{1}{2}(n-l)]!\;[\frac{1}{2}(n%2Bl)]!}{(n%2Bl%2B1)!}

\right]^{\frac{1}{2}} .](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d55c9b457e72fc64486c16a8bb4263f8.png)

![\left[{d^2 \over dy^2} - {l(l%2B1) \over y^2} - y^2 %2B 2n - 3 \right] v(y) = 0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/22fdf26fbe97605be7274a187d4405a3.png)

![\left[{d^2 \over dy^2} %2B 2 \left(\frac{l%2B1}{y}-y\right)\frac{d}{dy} %2B 2n - 2l \right] f(y) = 0,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/00e4d56142dcea2ff182e40049c9f27e.png)

![\frac{N^2_{nl}}{2\gamma^{l%2B{3 \over 2}}}

\int^\infty_0 q^{l %2B {1 \over 2}} e^{-q} \left [ L^{(l%2B\frac{1}{2})}_{\frac{1}{2}(n-l)}(q) \right ]^2 \, dq = 1.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7eef9d82d361bed3c1c3eb73815ae679.png)

![\frac{N^2_{nl}}{2\gamma^{l%2B{3 \over 2}}} \cdot \frac{\Gamma[\frac{1}{2}(n%2Bl%2B1)%2B1]}{[\frac{1}{2}(n-l)]!} = 1.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e0ed99622ed4cf2213ab151ff276702f.png)

![\Gamma \left[{1 \over 2} %2B \left( \frac{n%2Bl}{2} %2B 1 \right) \right]

= \frac{\sqrt{\pi}(n%2Bl%2B1)!!}{2^{\frac{n%2Bl}{2}%2B1}} = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}(n%2Bl%2B1)!}{2^{n%2Bl%2B1}[\frac{1}{2}(n%2Bl)]!},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e148d6cee440d113d8565ad7844ea5e9.png)

![N_{nl} = \left [ \frac{2^{n%2Bl%2B2} \,\gamma^{l%2B{3 \over 2}}\,[{1 \over 2}(n-l)]!\;[{1 \over 2}(n%2Bl)]!}{\;\pi^{1 \over 2} (n%2Bl%2B1)! } \right ]^{1 \over 2}

= \sqrt{2} \left( \frac{\gamma}{\pi} \right )^{1 \over 4} \,({2 \gamma})^{\ell \over 2} \, \sqrt{\frac{2 \gamma (n-l)!!}{(n%2Bl%2B1)!!}}

.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8b025e0e2e1fdc24a941ddb767452c6f.png)

![\left[ -\frac{1}{2} \frac{d^2}{dy^2} %2B \frac{1}{2} \frac{l(l%2B1)}{y^2} - \frac{1}{y}\right] u_l = W u_l .](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/63ccca13fb8b2a70038b06a6365b2c8e.png)

![\left[ \frac{d^2}{dx^2} -\frac{l(l%2B1)}{x^2}%2B\frac{2}{\alpha x} - \frac{1}{4} \right] u_l = 0,

\quad \text{with } x \ge 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3600223130df1a34be9966290285a61c.png)

![\left[ x\frac{d^2}{dx^2} %2B (2l%2B2-x) \frac{d}{dx} %2B(\nu -l-1)\right] f_l(x) = 0 \quad\hbox{with}\quad \nu = (-2W)^{-\frac{1}{2}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bfd8493566970d2d0c0469a6f282e5c2.png)

![N_{nl} = \left[\left(\frac{2Z}{na_0}\right)^3 \cdot \frac{(n-l-1)!}{2n[(n%2Bl)!]^3}\right]^{1 \over 2}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2fcd39cfa745b55a546676ce2368a4a1.png)

![\int_0^\infty x^{2l%2B2} e^{-x} \left[ L^{(2l%2B1)}_{n-l-1}(x)\right]^2 dx =

\frac{2n (n%2Bl)!}{(n-l-1)!} .](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/71b6024fd677e37d9bafe073c26b0929.png)